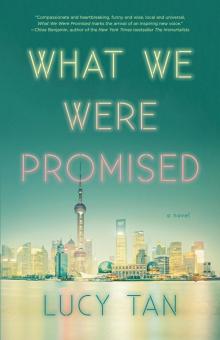

What We Were Promised Read online

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Copyright © 2018 by Lucy Tan

Cover design © 2018 by Lucy Kim

Cover photograph © Todd Antony / Galley Stock

Author photograph by Sarah Rose Smiley

Cover copyright © 2018 by Hachette Book Group

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

First Edition: July 2018

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-43721-9

LCCN 2017944470

E3-20180611_DA_NF

Table of Contents

Cover

Title

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

Shanghai 1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Newsletters

For my parents,

and theirs

谭凌实

陈朝霞

谭明儒

杨稔年

陈恩泉

罗锡贞

Shanghai, 1988

It wasn’t the plane Lina feared, but the sky above the airfield. Acres of space unbroken by trees or buildings made Lina nervous. They made her feel as though she would float away.

From where they stood in the Shanghai Hongqiao airport terminal, Lina and Wei watched the planes move around the tarmac. Men in reflective jumpsuits directed traffic with semaphores, but it seemed a miracle the huge machines weren’t crashing into each other without physical barriers to stop them.

“What do you think?” Wei asked, pressing his fingers against the glass.

“It reminds me of a funeral,” Lina said. “Like in American films. Those big, shiny cars. What do you call them?” It was an odd word; she had just learned it. “Hearses. The planes look like a fleet of hearses.”

“That’s no way to think of it,” Wei said, his smile waning.

Lina hadn’t meant to be gloomy, only meant to say that she was impressed by the carriers’ power, their solemn elegance. They looked like the kind of vehicles that would take you someplace you would never come back from.

When they finally boarded the plane an hour later, the first thing Lina noticed was the smell of foreign cigarettes—a lighter, sweeter scent than Chinese tobacco. She didn’t know for sure what American cigarettes smelled like, but the scent matched her idea of America, the way long legs matched blond hair. She gripped her husband’s hand as he led the way down the aisle.

“Let’s just enjoy ourselves,” he said. “Here, give me your bag.”

They had lucked into a row of three empty seats. Wei helped Lina buckle into the middle one, but before he could return to his own by the window, she stopped him.

“Wait. Switch with me.”

If she was going to leave, she would say a proper good-bye to her home country. It felt wrong that her final glimpse of China would be of Shanghai, a city to which she was a stranger, and not her little house in the suburbs of Suzhou or the warm, tree-lined campuses of Wuhan. Not looking down at the one person whom she had not truly been ready to leave. Lina felt calmer now that the evening was growing dark, the wash of blue like a safety net thrown across the sky.

Soon, the pilot’s voice came over the PA system, and then the plane started to move. Wei took her hand. He wanted this to be an experience they shared together, but she could not share it with him. Would not. These last moments she’d save for herself, to grieve the passing of a future that would never play out. She couldn’t help it; Qiang’s face flashed across her mind, and instead of fighting it, as she had been for the past few days, she let herself hold on to it, even closed her eyes to help herself remember. A dusty room filled with sunshine. Her breathing heavy from climbing the stairs, and all around her, the sound of mulberry leaves being torn apart by tiny mouths. Qiang leaning in close, his hair in his eyes, lifting a silkworm to Lina’s face.

“It’s perfectly safe,” Wei said. “I promise.” His voice sounded as though it came from hundreds of meters away.

She focused on thoughts of the lake. The breeze coming in both cold and hot at the same time. The shadow of a boy leaping from the water’s edge, his back shiny and curved like a blade.

The plane began to lift. As Lina’s center of gravity changed, she was pressed flat against her chair. Outside, the ground slipped from view. They were gaining speed, and soon they would be far away. Far enough to cross time zones, the concept of which still made Lina’s head spin. In China, a person’s day might start with the sun a little higher or a little lower than that of his countrymen, but their lives were all marked by the same clock, no matter how far apart they lived. America had six time zones. Lina’s father called it the land of dreams, and so it seemed. For what other country would aspire to occupy the past, present, and future, all at the same time?

Shanghai

2010

1

One day you’ll walk into a suite and find doors closed to you—the second bedroom, the study, the many closets. We had guests over, Taitai will say. We went ahead and tidied a little ourselves. But that won’t explain the jade missing from the display case or her designer shoes gone from the entryway. In the master bedroom, someone will have done your job, badly. A bureau cleared, its contents stuffed out of sight; the bed made so that the sheets still hang loose from the mattress. Taitai will stay in the next room with the baby. She will not come out until after you’ve gone, but for once, she’ll be listening to you—listening for the sound of your feet. With fewer rooms to clean, you’ll finish up quick and wheel the cart back through the service entrance to the laundry hall. That’s when you’ll take out your phone and text your loved ones the news: you’re about to be accused.

When Sunny had heard this speech from Rose on her first day of work, five years ago, she hadn’t thought much of it. She’d assumed it was just an old housekeeper’s attempt to scare her new partner, a way of saying I know what’s what and you know nothing. Sunny was expert at knowing nothing. Where she’d come from, she’d spent more than a year as a professional odd-jobber, a forever-apprentice hired out by her parents for gigs around her hometown. She’d fixed motors with the handyman and skinned vegetables for restaurant stews. She’d washed l

aundry and delivered cargo—rubber tires and concrete slabs and dead chickens in need of plucking—on a bicycle, her load sometimes a few hundred pounds more than her own weight. In every job, she had been trained by someone like Rose, a person too old to learn new skills and who craved recognition for the ones she already had. This kind of trainer expected Sunny to learn quickly and yet resented her for doing so. Sunny was tired of being a novice. She was determined to be great at something, and cleaning homes was as good as anything else. Na, it would be different here. Full-time job. No end date.

Rose had led Sunny down the hall to the changing room, listing the shortcomings of the hotel and serviced apartments. The guests and residents were wealthy and therefore very particular. Management was unfriendly, at best. They hired English speakers for the front desk, and those employees looked down on the rest of the staff. Worst of all, though, were the accusations of theft. They were easy to make and difficult to defend against. Any one of the maids could be replaced faster than you could fry up an egg for mei guo lao breakfast. There wasn’t any shortage of migrant labor.

“Where is your hometown?” Rose asked, opening a locker and retrieving her uniform from its shelf.

“Hefei,” Sunny replied. The outskirts, she didn’t say. Rose looked Sunny up and down, her expression making it clear that she understood exactly where she was from—the distinction wasn’t necessary.

“Another one from Anhui Province. You will find many friends in this city.” As she spoke, Rose pulled on a khaki-colored tunic, black cotton trousers, and standard-issue cloth shoes. She was in her forties but looked older. Her hair was shot through with silver, and the skin on her face was pocked as an orange rind. With practiced twists of her wrists, she rolled up the sleeves of her tunic and adjusted her collar so that it sat comfortably on her shoulders.

Sunny had put on her own uniform before leaving the house that morning, but she had ridden from Hongkou to Lujiazui on her motorbike, and by the time she had arrived at the hotel the entire back of the tunic was drenched in sweat. In the air-conditioned changing room of Lanson Suites, she felt the polyester’s damp weight. Sweat had stiffened her bangs in flat strokes across her forehead.

“Where are your stockings?” Rose asked when she caught Sunny pressing a swollen heel against the metal lockers. “Xiao gu niang,” she called her, even though Sunny was nearing twenty-nine, had not been a girl for some time. “You’re lucky to have been partnered with me. Some country girls learn quick; others are back on the job market within a week. We’ll see which kind you are.” From inside her cubby, Rose pulled out a pair of nude-colored hose and handed them over.

Each of the housekeeping supplies had its own place on the cart. The bottom shelf held cleaning fluids, towels, and toilet paper, which Western residents used with incredible speed. The top shelf was filled with boxed soaps, tissues, pouches full of needles and coils of colored thread, plastic combs with teeth too fine for thick Chinese hair like their own. With these, they stocked only the short-term hotel rooms—the permanent residents preferred toiletries imported from abroad. When the cart was ready and both women fully dressed, Rose reached into a cabinet and pulled out a plastic bin full of name tags. “Here,” she said. “Pick one.”

Sunny couldn’t read English but did not want to ask Rose for help. This moment felt too important, too private. Years later, she would remember digging through the bin, not knowing what she was looking for, but knowing it was right the moment she found it: S-u-n-n-y. There was something balanced and generous about the shape of that S, and she liked the way the double n’s looked like the u turned upside down. The letters reminded her of a row of children playing leapfrog. She especially liked that the tag was still in its plastic wrapping. It meant that no other maid had used it before, that she would be the first S-u-n-n-y to sweep Lanson Suites’ floors. That was something she had been looking forward to when she arrived in Shanghai—an identity all her own.

In the five years since her first day at Lanson Suites, Sunny had developed a way of moving about the residents’ homes that was quiet and deferential. She had learned each family’s habits and customs—the direction in which they stacked the dishes on the drying rack, the stuffed toys that were loved enough to have a permanent spot on top of a child’s bed—and by attending to these details, she had her own means of communicating with these families. She wanted them to see that she was a person who took pride in her work, who would go out of her way to make their lives run smoothly.

The housekeeping staff at Lanson Suites always went by their English names, even though none of them spoke English. Chinese names were too difficult for foreign residents to pronounce and carried too much meaning to be revealed to the Chinese speakers. When characters in a name were combined, they produced a complex of feelings and images. That was no good; the best thing for a housekeeper to be was forgettable. Better to take on the blankness of American names. Choose well—a flower, a tree, a month—and its prettiness might make you also seem faultless. They liked to think that giving themselves the right names could prevent them from being accused of stealing, but they knew it wasn’t true. Having an English name would not improve a person’s language skills, and without the language, they would always seem like intruders.

As a child, Sunny never imagined that she would end up in Shanghai. She was here because it gave her a life different from the one she didn’t want, one that would have been a matter of course in Anhui: more odd jobs, a second marriage, children, and restless old age. She had gone to extra lengths to protect her position, which was why, on the day Sunny was finally accused of theft, it came to her as a shock.

“I’m just reading what I see here,” the hotel manager had said, pointing to his clipboard. “Zhen Taitai told us there is no doubt the bracelet was taken by the cleaning staff. You and Rose were the only two with access to her bedroom these past four months, so until we find the bracelet, we’ll have to run security checks on you. Nightly.”

Sunny was glad that at least both of them were being accused; Rose had been accused before. At the end of their shift that evening, Sunny followed Rose to the back of the service hall, where they unzipped their bags and laid them on the table. The regular security guard wasn’t in, so the hotel manager’s son had taken his place. He was sixteen and seemed to be only pretending to know what he was doing. He picked open packets of tissue, unscrewed thermoses, and fingered the contents of their coin purses. When a text came through for Sunny, he even paused to read the message on the screen.

“Enough,” Rose said. She had two sons of her own, could sharpen her voice to make boys listen. The hotel manager’s son dropped the phone back into Sunny’s purse, where it lay glowing mutely into the fabric lining. She had been worried, earlier, about the next part, the part where he touched them. But his hand strokes over their bodies were quick and embarrassed. Sixteen, after all. In a place like this, with its badges and uniforms, it was easy to forget that their greater age could still be an intimidating factor.

When it was over, they were the only housekeepers left on the premises. Their shift had ended just as the sun set on the compound, covering the grounds in rose and gold, stretching shadows back as far as they would go. The service hall opened onto a stone path that led around the back courtyard and through a small sculpture garden, where European conquerors stood dumbly on their stone foundations, trapped in the darkening green. Past Lanson Suites’ painted iron fence, high-rises leaped up out of the ground, their glassy walls catching the last of the evening light. And though it wasn’t visible from where she stood, northwest of these was the iconic Oriental Pearl TV Tower—two reddish-purple spheres, one above the other, held high in the sky by cylindrical stanchions.

The first time Sunny had seen an image of the Pearl Tower was six years ago, when she was still living at home. On an errand to Hefei’s city center one day, she’d come across a trinket shop that carried postcards. As she was flipping through them, one postcard in particular caught her eye—a p

hoto of the Bund at night. Sunny’s eyes had immediately been drawn to the Pearl Tower’s alien presence. How unlike the drab, boxy buildings in Hefei. In that evening shot, the tower was lit, and each of its two orbs shone like a disco ball.

It hadn’t struck her as odd to see souvenirs of another city sold in Hefei. After all, Hefei was a city full of other cities’ leftovers—overstocked furniture, yuandan bags, and name-brand watches that were too expensive for anyone but tourists to buy. It was a city full of people who did not have the connections, start-up costs, or the guts to move to Shanghai, Guangzhou, or Beijing. Even its pollution was secondhand. Smog blew in every May and June from the surrounding lands, where farmers burned their crops in preparation for the next harvest year. Third-tier city though it was, Hefei was where Sunny had been wanting to move before luck swung her way. A year or two after stumbling across that postcard, Sunny got word that a neighbor’s cousin who had been working in Shanghai had gotten pregnant and was giving up her position at a luxury hotel. Sunny knew she had to act. She begged three months’ salary from her parents and took it to the neighbor’s doorstep. Put me in touch, she’d said. Qiu ni—introduce me. It had been out of character for Sunny to behave so rashly, to offer up all that money in the slim hope of landing a job. But never before had anything called to her the way that the Pearl Tower had. What she wanted most of all was to live in a place where she could look up at the sky every day and see something beautiful and more permanent than herself, the people she knew, and their own sorry circumstances.

Now the Pearl Tower was far from the flashiest building in the city. Over the past few years, Shanghai’s skyline had become crowded with lights and spires, and each had been designed to look grander than the last. Right there in the center of the photos was Lanson Suites Hotel and Residences. In the evening, its towers were all lit up like neon keyboards laid on their sides.

What We Were Promised

What We Were Promised